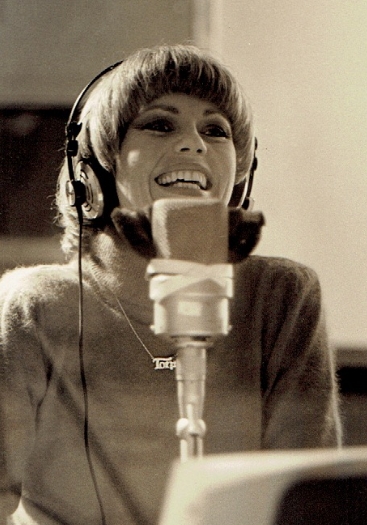

Toni Tennille: Hit maker and idol of the romantic hopeful

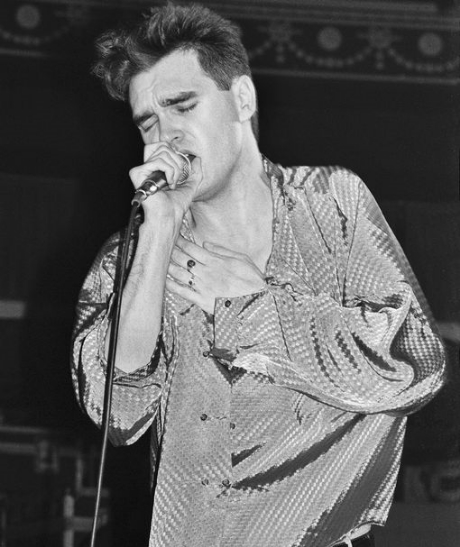

Morrissey: Hit-maker and idol of the romantic pessimist

Toni Tennille was introduced to Morrissey one rainy afternoon at an Indian restaurant in Orlando, Florida. Well, they didn’t exactly meet face to face, but it was the first time Toni ever heard about the notorious melancholic crooner, writer and animal-rights advocate who had fronted one of my all time favorite bands, the Smiths.

Toni, who is my aunt, was treating my boyfriend Michael and I to an early dinner. We were just digging in to our steaming dishes of palak paneer and kofta korma when the owner of the restaurant stopped by our table to say hello. He was an affable English guy in his mid-40’s, close to my own age, with pale skin, a thick east London accent, and a gelled, pompadour hairdo. On his black tee shirt, written in white cursive font, were the words “je suis Morrissey.”

“Morrissey!” I said, pausing mid dip into a bowl of chutney relish. “I love the Smiths!”

“Really?” the owner said, clearly delighted that I understood his shirt’s message. “I just saw Morrissey in Atlanta a few weeks ago. He was amazing.”

My aunt, puzzled, looked back and forth from me to the owner. “Morris who? What on earth are you talking about?”

I explained that Morrissey had been the lead singer of a band called the Smiths, and that he still recorded and performed as a solo artist.

“I’ve seen him over twelve times!” gushed the owner.

“Wow,” said Toni. “You are a big fan. What kind of music does he do?”

Me, my boyfriend, and the owner looked at each other.

“Well,” I said. “His music has lots of jangling guitars…and the vocals are sort of dark…but really funny, too.”

“Dark but funny?” Toni repeated.

“Artsy pop that came out of Manchester in the mid-‘80s,” Michael said, which I knew would mean absolutely nothing to my aunt. She gave him a blank look. “You could say Morrissey is a kind of modern day crooner,” he elaborated. “With poetic ambitions.”

“He sings the type of music disaffected teenagers crave,” I said. “Just like I did when I was young.”

“Morrissey is an absolutely brilliant songwriter,” the owner added.

That got my aunt’s attention; she, too is considered a brilliant songwriter. “Well then,” she said. “I have to hear this Morrissey!”

That’s one of the reasons why I just love my aunt. Most people may think of her as strictly ‘70s pop, but she has a deep, genuine interest in all kinds of music.

“I’d love to play you some Morrissey, Toni.” I said. “Why don’t I bring some Smiths records over to your house soon and we’ll have a listening party?”

“Wait,” said my aunt, confused. “Who are we going to listen to, the Smiths or Morrissey?”

Since the owner was standing there I was careful with my response. “I do like a lot of Morrissey’s solo work, but I’m really more of a Smiths fan. You’re still very much hearing Morrissey if you listen to the Smiths.”

“And with the Smiths, you also have Johnny Marr in there on guitar,” Michael added. “The juxtaposition of his playing and Morrissey’s vocals is really what makes their music so great.”

“Who’s Johnny Marr?” said Toni.

Later on the drive home I put on The Queen Is Dead, my favorite Smiths album. As I listened I began to think about the kind of music that had made my aunt famous in comparison to the Smiths post-punk guitar-driven style that had so captivated a certain sector of my generation. The songs Toni wrote as part of the ‘70s music duo Captain and Tennille were born and bred for the mainstream airwaves, romantic and upbeat, many becoming number one hits that helped define that decade.

But if you scratch through the glossy pop veneer, many of those songs have the same kind of plaintive, human longing that so many of Morrissey’s songs do. In her hit song “The Way I Want to Touch You,” which Toni wrote, she sings of her intense aching to be emotionally closer to the man she loves (yes, that would be the Captain) but he won’t let her. Morrissey is much less coy when he evokes similar frustrations in “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want,” but the basic idea is pretty much the same. These are two songwriters who are, for a lack of better words, pleading to be loved.

Toni had told me she used to get fan mail from people who wrote that her music had helped get them through dark times. Similarly, when I was a depressed teenager, listening to the Smiths had helped me sort through my own problems. Like lots of introverted, artsy kids who felt misunderstood in the materially lucrative but soulless American eighties, their albums became a kind of touchstone in my lonely life. I’d let the records play on repeat as I sat in my open window at night, looking out over the dark Tennessee hills, wishing I could be anyplace but where I was.

As a misunderstood youth growing up in dreary, Thatcher-era Manchester, Morrissey felt that way too--and you can piece the story together through his woebegone lyrics. Poetically melancholic but never outright weepy; wickedly funny but consistently mirthless—the Smiths' songs were, to me, a kind of teenage lullaby. The sound of Morrissey alternately howling and crooning over Johnny Marr’s shimmering guitars sent a sort of coded message that I wasn’t alone. That although life was all at once ridiculous and painful and confusing, there was a light at the end of the tunnel. And that while my emotions were being whipped to a head by adolescent angst, I really shouldn’t be taking it all quite so seriously.

I knew from co-writing Toni’s memoir that she had once been a mopey teenager, too, trying to come to terms with a dysfunctional family life upset by an alcoholic father. Who, I wondered, had been her Morrissey? Whose music and voice had given her comfort when she escaped from the rest of the family behind her locked bedroom door at the Tennille home in Montgomery, Alabama? The more I thought about it, the more I wanted to know.

Click here to read Part Two